Developing and Testing Stochastic Filtering Methods for Tracking Objects in Videos

Valentina Staneva

My name is Valentina Staneva and I work as a data scientist at the eScience Institute at University of Washington. I am an applied mathematician who develops methods to extract information from diverse datasets. Most of my experience is in the domain of image processing and its biomedical applications. This case study describes the workflow of a particular project whose goal was to develop and test new algorithms for tracking objects in videos which aim to preserve the original structure of the objects. This research was done while I was a graduate student at the Center for Imaging Science, at Johns Hopkins University, and was motivated by the task of tracking heart motion in cardiac images. I believe it reflects a typical experience of an applied mathematician working on biomedical imaging problems.

Workflow

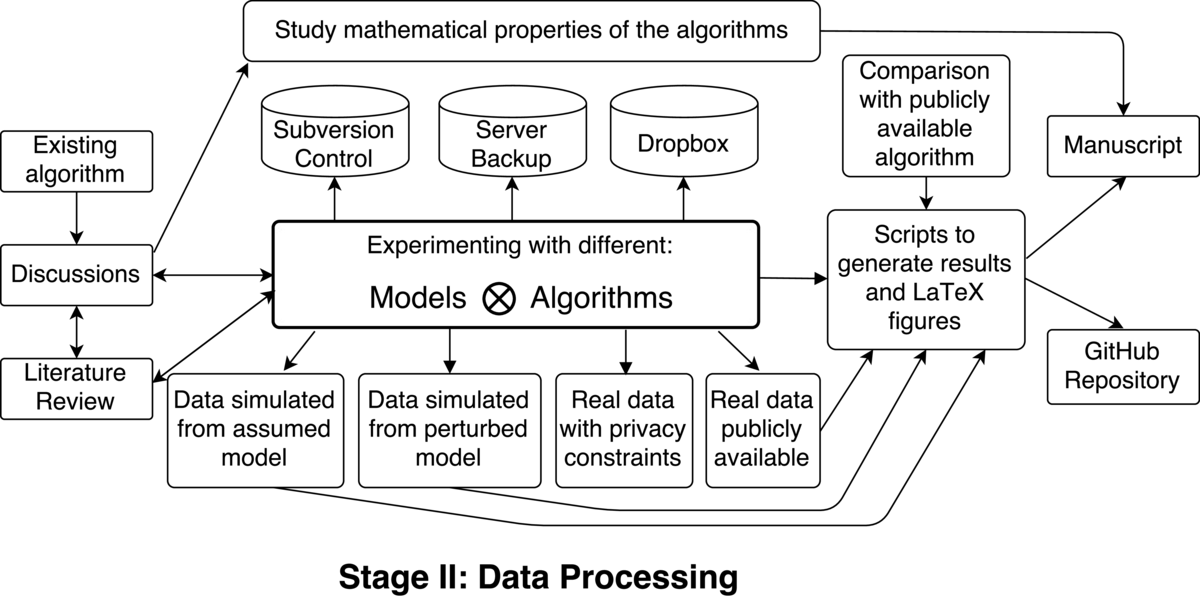

This work follows a typical flow for problems in my field: motivated by an existing algorithm, we aimed to extend it to processing sequences of images (as opposed to a single image). Usually the process involves experimenting with different models of the data and different inference algorithms (intertwined with discussions with my advisor and literature reviews). The various combinations of these models and algorithms can be tested on three main types of datasets:

This work follows a typical flow for problems in my field: motivated by an existing algorithm, we aimed to extend it to processing sequences of images (as opposed to a single image). Usually the process involves experimenting with different models of the data and different inference algorithms (intertwined with discussions with my advisor and literature reviews). The various combinations of these models and algorithms can be tested on three main types of datasets:

a dataset simulated from the assumed model: since the dataset is coming from the "correct model", this experiment is mainly testing the performance of the inference algorithms

a dataset simulated from a model which deviates from the assumed model (in some interpretable way): this experiment is testing the robustness of the algorithms

a 'real' dataset: a video of a moving object; this tests the applicability of this methodology in practice

This results in exploring quite a lot of different setups and most of the research time is spent at this stage (it can take from weeks to several months to implement and test a specific formulation). The work was performed on an account on a university server, which was sequentially backed up. I also used Subversion for version control and stored my files in a Dropbox folder (which has its own version control). Luckily, I never lost a file, even when our server got hacked.

In general the evaluation of these algorithms on real data is difficult. There are no standard testing datasets, and it is hard to design ones as different image sequences describe different processes, and some algorithms perform well in some situations and poorly in others. One usually considers a range of typical tracking hurdles and checks whether a given algorithm can overcome them. Since there is no one final metric to submit this requires storing all the results from all the experiments. In the end I saved all the code (written in MATLAB), data, and experiments in a folder, which provides everything necessary to regenerate the results in our manuscript with a few simple commands. When reviewers requested an additional plot to be included in our article, I could easily obtain it from the original data. We also selected a journal which does not prevent us from posting the preprint of the article elsewhere and stored all the supplementary materials on GitHub.

The workflow also contains a parallel path in which one studies the mathematical properties of the models and algorithms. For example, we aimed to develop algorithms which preserve the topology of the tracked objects, and we proved that our framework ensures that, thus eliminating the need to test this property in multiple cases. Sometimes it is possible to guarantee the performance of algorithms even without implementing them, which makes reproducibility of mathematical research quite easy!

Pain points

1) Private data: some of the motivation for this project was driven by the need to process a specific cardiac dataset and perform statistical analysis on the obtained results. I initially tested the algorithms on this dataset, however, eventually I was not allowed to use it in my publication due to some privacy concerns. I resorted to searching for a public cardiac dataset which turned out extremely difficult to find: a website which aimed to maintain a public database of cardiac images was permanently down as the creator left the field. One good source for public biomedical datasets is MICCAI conference challenges: they contain datasets on which to assess methods for solving very specific problems. The drawback is that sometimes the datasets are not complete, as they are designed to solve a particular challenge: for example, the dataset I obtained from an image segmentation challenge did not contain ground truth relevant to the tracking problem.

2) Volume (Storage): when processing video sequences, an issue simply arises from the size of the produced outputs. If I generate many experiments (which is inevitable when performing MCMC simulation) I have to store many videos. Without a ground truth, I could not store just a small measure of mismatch instead of the whole sequence. GitHub's policy does not accept files larger than 100MB. This caused difficulty when trying to upload even only the input data to the repository. This makes it hard to keep code and data together and easily accessible.

3) Randomness: working with Monte Carlo simulations results in different outputs every time the algorithms are applied. This requires the extra step of forcing the random number generators to produce the same sequence of random numbers. This procedure is not so simple when parallelization is involved: MATLAB (and similar scripting languages) usually do not have control over the order in which the separate threads are started and that results in extra randomness in the output. Further, attempting to generate multiple random streams simultaneously results in producing identical sequences of pseudo-random numbers (the seed is based on the current CPU time) which corrupts the Monte Carlo algorithm. One solution is to generate all random sequences that would be needed in the parallel threads in advance, but this requires modification of the programs themselves. Working with random outputs also makes it hard to generate unit tests: we only have asymptotic results of what the outputs should be, so it is difficult to set the confidence intervals for the outputs even with simulated data.

4) Backup: I used Subversion for version control of this project. I wanted to use the integration with the Nautilus file manager that Subversion was providing. It turned out it was buggy (it was a new feature at that time) and not all commits were recorded through the graphical interface: quite dangerous! I learned that it is more reliable to use explicit terminal commands with version control systems.

Key benefits

One of the main advantages of this workflow is that all the code was written in one language without resorting to external libraries and toolboxes. Usually core language functionality changes much more rarely than add-on packages, which makes software better sustainable in the long run and across platforms.

Our approach of encoding certain mathematical properties into the developed algorithms also makes the research more robustly reproducible under deviations of the original set-up.

Questions

What does "reproducibility" mean to you?

"Reproducibility" has two meanings for me:

(1) "Exactly reproducible" - when a result can be regenerated exactly as suggested given the same set of inputs and parameters. For example: a manuscript is "exactly reproducible" when one can provide some scripts and environment which with a press of a button (or an explicit set of instructions) can generate all the figures and calculations in the manuscript.

(2) "Approximately reproducible" - when a result or similar performance can be generated with similar or different methods than the one proposed on the same or possibly slightly different data. Often in science, the goal is to test a hypothesis and the methods to achieve this do not matter, it is actually better if the same hypothesis is supported through different approaches. Further, the data on which the study was performed might never be observed again, so it is not so important to reproduce the results on these data, but it is important to produce similar results on similar data. We are interested in the robustness of the methods and the conclusions, and a better term may be "robustly reproducible".

This case study directly addresses the first type of reproducibility, but it explores also a bit of the second interpretation.

Why do you think that reproducibility in your domain is important?

I find two main reasons for the importance of reproducibility in my domain:

Personal: working with image data is often quite involved, and one does not want to do things twice, but it is often necessary, and in that case it is better to have an automated process to repeat experiments.

Public: there is overabundance of algorithms and studies but it is hard to use them in practice, because there is no simple way to reproduce the results (one usually needs to reimplement the algorithms or redo the studies). So if one wants their research to be useful outside their own group, they should first ensure it is reproducible.

How or where did you learn about reproducibility?

I have been learning by myself. I believe some short reproducibility workshops would have improved my experience substantially (for example, learning about git/GitHub, virtual environments and light virtual containers).

What do you see as the major challenges to doing reproducible research in your domain, and do you have any suggestions?

Working with biomedical data one often faces privacy and storage challenges. Another problem which I did not encounter but I know is persistent in the field is the use of too many external software packages to preprocess the data: some of them are supported only by specific operating systems, or require manual operation. This makes it challenging to automate the workflow. In an attempt to improve performance on large datasets, researchers often use elaborate C++ programs which are hard to interpret and extend.

What do you view as the major incentives for doing reproducible research?

I think the incentives should be personal and based on the understanding that this would improve the workflow and this is how research should be done. Unfortunately, the time and efforts spent on creating reproducible research are not very well awarded.

Are there any best practices that you'd recommend for researchers in your field?

Be reproducible every day! It is much easier to perform reproducible research than making your research reproducible (after it was already performed).

Would you recommend any specific resources for learning more about reproducibility?

Some useful resources have been compiled by the eScience Reproducibility working group: http://uwescience.github.io/reproducible/

Other resources: https://github.com/Reproducible-Science-Curriculum

Coursera Class: https://www.coursera.org/course/repdata