A Statistical Analysis of Salt and Mortality at the Level of Nations

Kellie Ottoboni

My name is Kellie Ottoboni. I'm currently a PhD student in the Department of Statistics at UC Berkeley and a Data Science Fellow at the Berkeley Institute for Data Science. My research focuses on nonparametric statistics, causal inference, and applications in health and social sciences. The project I describe in this case study is an investigation of the association between salt consumption and mortality at the level of nations.

Workflow

This project started as a collaboration between my advisor and a professor of public health at UC Irvine, along with one of his students. I became involved after our collaborators had begun putting together the dataset. The data consists of demographic and socioeconomic variables, as well as gender-specific estimated sodium, alcohol, and tobacco consumption for 38 countries. The data were pulled together from several sources and the variables are described in a text file.

This project started as a collaboration between my advisor and a professor of public health at UC Irvine, along with one of his students. I became involved after our collaborators had begun putting together the dataset. The data consists of demographic and socioeconomic variables, as well as gender-specific estimated sodium, alcohol, and tobacco consumption for 38 countries. The data were pulled together from several sources and the variables are described in a text file.

The first step was to decide what data we needed to answer the question: does salt consumption have an effect on a nation's life expectancy at age 30? We decided that the best way to address this would be to consider males and females separately, and to use a country as its own "control" by looking at the changes in life expectancy, alcohol, tobacco, and sodium consumption, and economic variables over time. We had the variables we needed, but gender-specific alcohol data were missing for one year. These couldn't be obtained so we imputed them based on gender ratios in each country and overall consumption that year. We also had to remove countries with missing data on life expectancy, the outcome of interest. In addition to the R code implementing these steps, I described them in a LaTeX report as I went along.

The method of analysis was a novel hypothesis test that I have been developing with my advisor. The premise of the method is to predict the outcome of interest, change in life expectancy, using all covariates except the treatment of interest, sodium. If sodium is still related to life expectancy after controlling for known health predictors, then sodium consumption will be associated with the residuals of the model. This is simply a mathematical fact: some of the variation that the model cannot explain will be associated with sodium. But how large of an association is statistically significant? We answered this question using nonparametric permutation tests. After discussing how our approach might answer the problem at hand, I wrote R code for the two main steps in the algorithm: the model selection and the nonparametric test of association. I had already written code for our proposed statistical method in R package format in a public GitHub repository, so I added the new code from this project into the package. I developed the code iteratively by running it on our dataset and checking that the output looked sensible. This isn't the best way to write code: ideally, I would have invented simple test cases and checked my functions against those.

After writing each component of R code, I combined all of the preprocessing, analysis, and plot scripts into an R Markdown file. knitr allows you to compile R Markdown, R code chunks interleaved with markdown text, into a PDF or HTML document. This way, I could send my collaborators the results quickly and in a user-friendly format. I posted all the scripts, data, and the compiled HTML document in a public GitHub repository dedicated to this project.

At this point, we were unsatisfied with the scope of the analysis and wanted to ask more questions. In particular, we wanted to run the same test of association but use tobacco and alcohol in place of sodium. These analyses would serve as a "sanity check" that the method performs as expected. Given that we know that both alcohol and smoking have negative effects on health, we would expect to find a negative association between the model's residuals and alcohol and tobacco use. The original dataset included alcohol consumption per capita, but no measures of tobacco use. This required our collaborators at UC Irvine to gather this data from an existing journal article. After receiving the tobacco usage data from them and performing the model-based matching analysis with it, we realized that the measure of smoking that we used was not a good measure of a nation's overall tobacco consumption. We again gathered different tobacco data and ran the analysis one last time. Since the R scripts had already been written, redoing the analysis with each version of the data amounted to changing a few lines of code. I kept each version of the data used and named them according to the date when it was sent to me.

We believe that we have done all the statistical analysis that we need to answer the scientific questions that we posed. The analysis portion of the project took about six months to complete. Our collaborators are preparing a manuscript. We are using LaTeX and communicating by email.

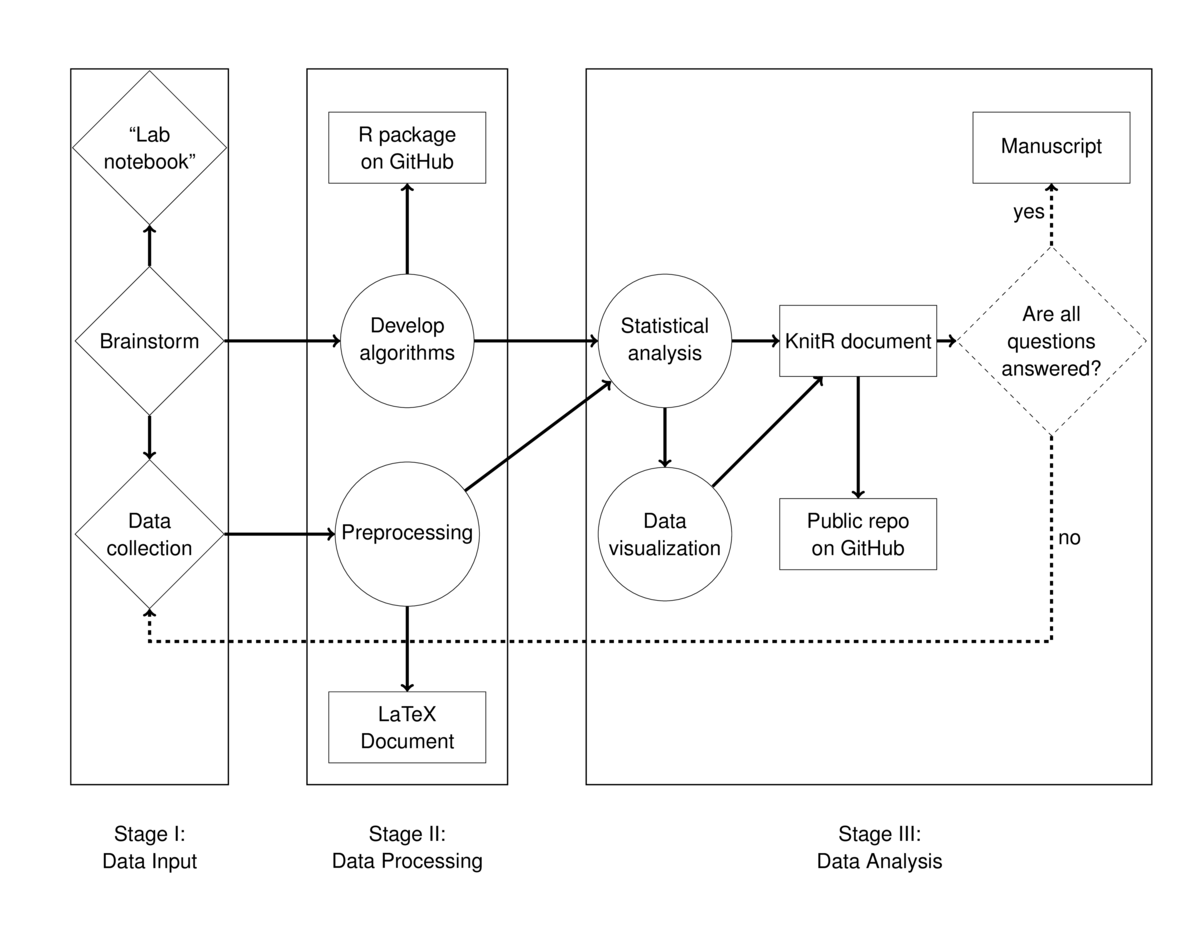

The workflow diagram distinguishes three types of activities: thinking and planning steps are marked with diamonds, action and implementation are marked with circles, and documentation and outputs are marked in rectangles. While arrows point to the right and boxes separate the three stages of the workflow, this is a bit artificial. In my experience, there is a lot of iteration involved in applied statistics projects. In addition, the number of nodes in each stage is not reflective of the amount of time spent. The majority of my time was spent planning and documenting. It was quick to make minor changes once the preprocessing and analyses were scripted.

Pain points

A seemingly trivial problem I struggle with is keeping track of files. Using git certainly simplifies the version control aspect of file organization, but that doesn't help when I've forgotten where I put a chunk of code I wrote two weeks ago. Around the beginning of this project, I started keeping a "lab notebook" to organize my thoughts on all the various projects I'm doing. I keep a folder of text files just for myself where I jot down the date, ideas and concerns, notes on what work I've done, and the names of files or folders where I saved that work. It has helped tremendously when I need to remind myself things about a project, and it's also a nice way to archive meeting notes and save ideas that I might want to share with collaborators later on.

A pain point particular to this project was trying to encourage my collaborators to use the GitHub repository. Ultimately, we ended up sending data and results back and forth by email. Pushing updated data and results to the repository would have been more efficient.

The data collection part of the project was opaque. Our repository does not include any scripts used to collect the data from various databases and journal articles or scripts to merge these data sources. At one point, under pressure of a deadline, I manually entered tobacco consumption figures into an Excel spreadsheet. All the preprocessing and analyses of the data are reproducible, but the process of collecting the data is not.

Key benefits

The biggest advantage of a reproducible workflow is efficiency. There were many iterations of the analysis for this project. By having preprocessing, analyses, and results written in the same document, it was easy to make small changes and ensure that they appeared throughout the report.

Incorporating the main functions for this analysis into an R package with larger scope will be beneficial in the future. The functions I wrote for hypothesis testing here are well-documented and uniform in their style, inputs, and outputs. Having them all in a package on GitHub makes it easy for anybody who reads our paper to install the package and replicate the results.

Key tools

RStudio and knitr were key for this workflow. This was my first time using knitr and I am pleased with the quality of the reports I created to share the results with my colleagues. All steps of the data analysis are in the documents, alongside my commentary and explanation of the steps. I hope that this makes the statistical methods transparent to my collaborators and future readers. Additionally, having all the tables and figures in one place will make it easy to put results into the manuscript.

Questions

What does "reproducibility" mean to you?

I think that a data analysis project is reproducible if there are enough breadcrumbs (in the form of code and instructions) for anybody to recreate the analysis from start to finish. In another sense, a project is reproducible if someone can carry out a different analysis on the data and arrive at qualitatively similar conclusions.

Why do you think that reproducibility in your domain is important?

Researchers tend to blame the "reproducibility crisis" on statistics, and in particular p-values. It's our job as statisticians to fight this claim by making statistical analyses as correct and as transparent as possible, so people know exactly where their p-values are coming from.

How or where did you learn about reproducibility?

I learned some of these practices from other students in my department and the rest were self-taught using resources on the internet.

Are there any best practices that you'd recommend for researchers in your field?

Explain every step in the data preprocessing and analysis carefully and thoroughly. Document and comment code liberally. Make code and data publicly available.

Would you recommend any specific resources for learning more about reproducibility?

Hadley Wickham's R Packages book is an invaluable resource. He demystifies the R package and shows how to use RStudio to make the workflow smooth and efficient.