Producing a Journal Article on Probabilistic Tsunami Hazard Assessment

Randall J. LeVeque

My name is Randy LeVeque and I am a Professor of Applied Mathematics and one of the core developers of the open source GeoClaw software package for modeling tsunamis and other geophysical flows. Recently we have been using this software to study new approaches to probabilistic tsunami hazard assessment (PTHA), in which the goal is to take some probability distribution of possible future earthquakes that might cause large tsunamis and produce a probabilistic hazard map for a particular community, indicating which regions are most at risk and estimating the annual probability of flooding to a given depth at each point. This is complicated by the fact that the depth of flooding by a particular hypothetical tsunami depends on whether it arrives at low tide or high tide, and we have developed ways to incorporate this uncertainty.

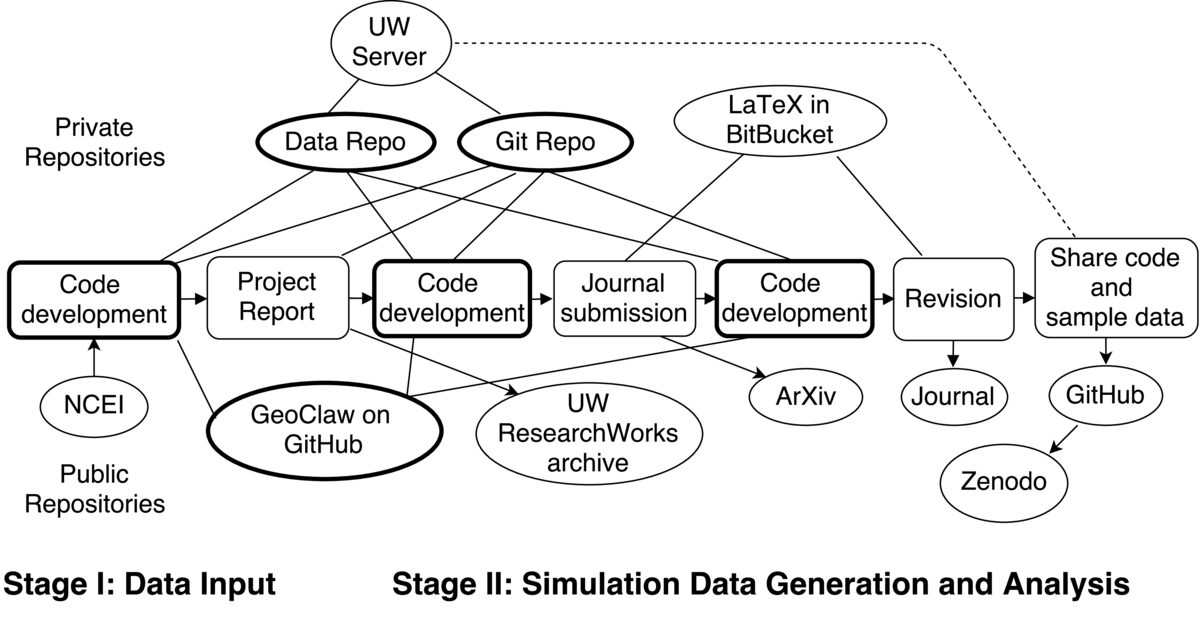

The workflow I will describe relates to a journal publication on this topic. Much of the research was originally performed as part of a consulting contract funded by a private firm, as part of a broader pilot study funded by the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA). We used version control for the code developed as part of this project that was initially in a private repository, along with the results of many tsunami simulations. A final project report based on this work was made available in our institutional repository, but was not published in a journal. We later improved the description of the methodology and performed additional computational experiments in the process of writing up a portion as a journal article. A variety of different private and public repositories were used in the course of this work, along with several platforms for sharing code, data, and the report and journal article.

Workflow

We first created a new account on the University of Washington (UW) campus computing system dedicated to this project that could be shared by the three collaborators, with sufficient storage for accumulating simulation results (and securely backed up by campus services). On this account we created a git repository that we could all access via ssh to use as our master repository for developing code, and eventually for writing the project reports. We did not use GitHub since we wanted a private repository and did not need the web features of GitHub (or Bitbucket) for this phase of the project.

We first created a new account on the University of Washington (UW) campus computing system dedicated to this project that could be shared by the three collaborators, with sufficient storage for accumulating simulation results (and securely backed up by campus services). On this account we created a git repository that we could all access via ssh to use as our master repository for developing code, and eventually for writing the project reports. We did not use GitHub since we wanted a private repository and did not need the web features of GitHub (or Bitbucket) for this phase of the project.

This project required using some large datasets that are openly available from the National Centers for Environmental Information (NCEI), in particular topography and bathymetry data for running the tsunami model and tide gauge data. We downloaded and archived some of this data on the UW account, but did not put it in the git repository since these did not need to be under version control. Instead we wrote shell scripts to rsync this data to each collaborator's laptop or other computers as needed. (rsync is a utility on unix-like systems to transfer and synchronize files). These scripts were kept in the git repository. Similarly we wrote scripts to rsync simulation results from the computer where the simulation was performed back to this account, along with some metadata. The new methods being developed for tidal uncertainty were implemented in Python code used for postprocessing the simulation results. One collaborator was doing most of the simulation runs, on several different computers, while another was developing and testing the postprocessing code, so rsync'ing the necessary data between laptops via the campus account was convenient and insured that it results were archived as we went along.

The shared campus account was also used to host webpages so that the visualizations produced from each simulation could be viewed by all collaborators. These webpages were also eventually used to share results with the project sponsors and reviewers of our preliminary report.

The private git repository was also used for writing the final report in LaTeX and collecting the final figures to go into the report. The third collaborator, who was less involved in the coding, was not completely comfortable with git and so we also used Dropbox for sharing and commenting on drafts of the report, but all changes to the LaTeX were made in the git version.

The final report was made available to the public by depositing it in the UW ResearchWorks Archive.

When we started working on the journal paper, we created a private Bitbucket git repository for collecting the code specific to the paper and for the LaTeX file. Bitbucket is similar to GitHub but offers free private repositories, requiring a paid account only for public repositories. By contrast, GitHub offers free public repositores, and charges for private repositories. The interfaces are similar and it is easy to transfer a git repository between them, or maintain copies on both services, so it is often convenient to use both for different purposes. The submitted preprint was also posted on the arXiv, a widely-used preprint server from which it was available with open access.

The referees requested changes to the paper and some figures needed to be redone, which was easy to do since we had produced all figures with scripts in the git repository. The revised paper was developed in this same repository, along with the authors' responses to the referees.

After the revised paper was accepted by the journal, we created a new public GitHub repository for the code and small datasets needed to reproduce some of the figures in the paper that illustrated the basic methodology. This repository was also linked to Zenodo, and a GitHub release was performed that triggered automatic archiving of a zip file of all the code at that stage, and assignment of a DOI.

In addition to the test problem for which we shared code, the final paper also contained some figures with results from the overall project, the probabilistic maps produced for Crescent City, CA using this methodology. Reproducing these results would require running roughly 100 tsunami simulations. We are fairly confident that we have all the code and data to reproduce these results if required, but we have not made this publicly available.

Pain points

Using rsync for large datasets worked fine once we figured out a good workflow and scripts, but is not ideal. A version control system like git that works well for large quantities of data would have been very useful.

Some data could not be shared and we also had to be careful about sharing preliminary results since emergency managers and the agencies involved are very sensitive about publicizing risk maps for specific communities before they have been properly vetted and agreed on.

Key benefits

This workflow proved to be very valuable for this long-term project in which many parts of the code and methodology were evolving. The initial project was followed by additional funding for a Phase II, in which the focus was on studying current velocities rather than only flow depth. This required re-running all the tsunami simulations with a modified version of GeoClaw. Having done all the initial work via scripts archived under git, it was relatively painless to redo these runs. In the meantime other changes had also been made to the GeoClaw code, and having both our code and GeoClaw under version control was very useful when comparing results.

Questions

What does "reproducibility" mean to you?

There were two distinct aspects of reproducibility important in this work. The original development of new techniques was performed in the context of a project that went on for several years and required running many tsunami simulations with the GeoClaw code for the probabilistic studies, each of which took several hours of computing time and produced large quantities of output data. During this time frame the GeoClaw software was evolving, along with our methodologies. GeoClaw is openly developed on the GitHub site. We needed to be able to compare new results with those computed previously, and be able to identify what changed in the software or our code in between, if necessary. For this aspect the goal was not to openly share all of our work or the results (nor were we allowed to, due to the nature of the project), but we needed to be able to reproduce results ourselves if necessary and keep the code under version control to identify changes.

The other aspect is that we wanted the particular new method written up in the journal paper to be accompanied by the Python code that implements the method and a sample set of data that was used to produce some of the figures in the paper. In this context we wanted the figures to be reproducible by a reader using this code, in hopes that this would aid others in understanding the methodology and adapting the code to solve their own problems.

Why do you think that reproducibility in your domain is important?

For researchers who develop new methods and algorithms, it is often important to be able to see the details that are in the code but don't make it into the paper, both to better understand the work and to find potential errors. It also facilitates comparing different methods for the same problem.

In natural hazards modeling, the simulation results may be used by engineers or policy makers to make decisions with public safety implications. Transparency and reproducibility are important aspects of accountability.

How or where did you learn about reproducibility?

My interest in the topic came out of frustration with the publications in numerical analysis (including my own) where it was impossible to reproduce published results or fully understand the implementation of new algorithms they describe. I became proficient with git initially through involvement in open source software projects.

What do you see as the major challenges to doing reproducible research in your domain, and do you have any suggestions?

Convincing collaborators to learn and use a common set of tools is sometimes a challenge, and some researchers are more willing to share code and data than others.

Some input data and/or results can not be shared publicly, so it may be necessary to selectively share data and perhaps have both private and public repositories.

What do you view as the major incentives for doing reproducible research?

Ability to easily modify and build on past work.

Ability to compare new approaches or software with past versions and determine what changes made a difference in results.

Facilitates collaboration.

Are there any best practices that you'd recommend for researchers in your field?

Using version control of some sort is the single most important first step.

Make a habit of cleaning up code used to produce final results so that it's well documented and all the necessary steps are clearly laid out. Then run through them from scratch if possible to insure that it works. Even if you don't plan to share it with others, your future self will thank you.

If you do share code and/or data, do so in an archival repository that issues a DOI, and attach a license.

Would you recommend any specific resources for learning more about reproducibility?

The UW eScience Institute Reproducibility and Open Science Working Group has developed some guidelines.

The 2012 ICERM Workshop on Reproducibility in Computational and Experimental Mathematics resulted in a final report with recommendations and additional links.