Validating Statistical Methods to Detect Data Fabrication

Chris Hartgerink

My name is Chris Hartgerink, I am an applied statistician at Tilburg University specializing in detecting potential data fabrication with statistical methods. As a PhD candidate I pay attention to my workflow in order to increase efficiency and ensure it applies modern tools to improve my research. My case study will revolve around a project where I assess the performance of statistical methods to detect both genuine and fabricated data. In this project, I collect genuine datasets and invite researchers to fabricate datasets, to which I apply statistical methods to detect data fabrication.

Workflow

Statistical methods can be applied to detect potential data fabrication, but their validity is unknown. Simulating how researchers fabricate data is impossible because we simply do not know how researchers actually fabricate. Anecdotal summaries of uncovered misconduct cases do exist but are not generalizable. In order to test the performance of statistical methods in an ecologically valid manner, I invited researchers to fabricate data for a study for which we also have genuine data. With this, we can test the validity of a set of statistical methods to detect data fabrication. More specifically, genuine data contains sampling variance, whereas fabricated data frequently contains insufficient sampling variance. An example of such an analysis is testing whether nonsignificant p-values are uniform distributed, or whether higher p-values occur more frequently than lower p-values (which is theoretically implausible).

Statistical methods can be applied to detect potential data fabrication, but their validity is unknown. Simulating how researchers fabricate data is impossible because we simply do not know how researchers actually fabricate. Anecdotal summaries of uncovered misconduct cases do exist but are not generalizable. In order to test the performance of statistical methods in an ecologically valid manner, I invited researchers to fabricate data for a study for which we also have genuine data. With this, we can test the validity of a set of statistical methods to detect data fabrication. More specifically, genuine data contains sampling variance, whereas fabricated data frequently contains insufficient sampling variance. An example of such an analysis is testing whether nonsignificant p-values are uniform distributed, or whether higher p-values occur more frequently than lower p-values (which is theoretically implausible).

At the beginning of the project, we had an initial meeting to detail specific aspects of the project. This meeting is crucial to determine and assign responsibilities, start discussion of ethical considerations, and how the project will be conducted. For this project the main points we discussed were (i) the ethical obligation to guarantee participants that they would remain completely confidential, given that they were technically required to breach ethical standards, and (ii) how to convince the participants that this study had justified reasons to request this behavior. We required the participants to generate data, and decided to not save any identifying information by default and permanently delete the identifying they gave us as soon as practically possible. We decided to motivate the participants with the study goal itself and reward them depending on whether we could detect their data fabrication with statistical methods. Several default points I like to address in this initial meeting:

Agree that research files will be publicly shared by default and proper arguments are needed to not share research files publicly (e.g., ethics committee restraints).

Agree that the publicly shared research files are put in the public domain (licensed Creative Commons 0), to maximize breadth and clarity with respect to reuse rights of the research materials.

Agree that the research manuscript will be shared as a preprint upon completion for improved peer feedback, and that the manuscript will be published openly and with an appropriate and clear reuse license only (i.e., CC-BY or CC-0, definitely not CC-BY-Non-Commercial).

Role assignment (e.g., project lead, fund raiser, analyst, who will check the analyses).

Specifying research project

The project-lead subsequently followed up with a draft description of the project and an initial draft of the research materials. These contents included a technical description of the design, hypotheses and theoretical framework, but also a draft of how the data would be analyzed. This increased transparency in the analytic methods increases accountability amongst authors. Explicating these methods is important because things that seem obvious might not be, and this helps get everyone on the same page (e.g., do we include covariates? Do we agree how covariates are measured?). After sharing these drafts and iteratively revising them, the experiment was submitted to the ethical committee for review, given that the study involves human participants. Considering that each university has different procedures, I will not elaborate on these here.

The files that are drafted after the meeting are included in a GitHub repository, which allowed for version control of the files, providing a logbook. These files were synchronized to an Open Science Framework (OSF; osf.io) repository to increase discoverability and shorter URLs to include in the manuscript. Version control can be compared to track changes for computer files, allowing you to go back in time and view what changes were made and when. With version control a logbook of changes is created, which improves the reproducibility of the research process if anyone is ever interested. My personal experience indicates that this logbook is rarely inspected (except in data audits), but it can serve as a handy reference when somebody asks you when a specific event occurred (e.g., when were the analyses programmed for the first time). Version control is most effective when started immediately after the initial meeting.

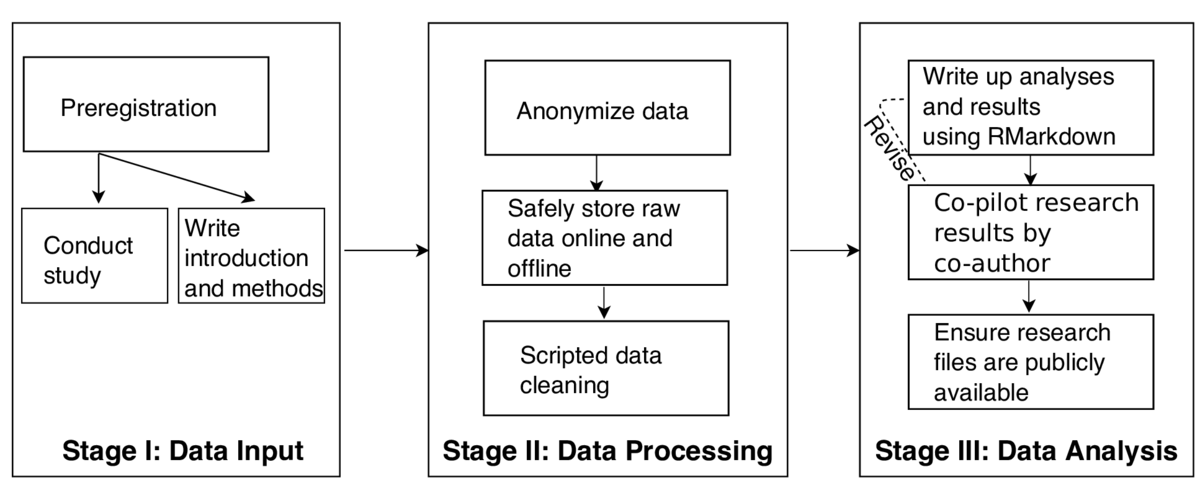

After the ethics approval was acquired, the version controlled research files were preregistered. This preregistration is done on the OSF. This preregistration makes an unalterable snapshot of the research files with a timestamp, which provided a confirmation that what we set out to do and expected was indeed a priori to actually conducting the study..

Following the preregistration, we actually conducted the study. Because our study ran for several weeks to reach the quotum of participants, I used that time to rewrite the preregistration into the introduction and method sections of the manuscript. Having planned this beforehand, I wrote my preregistration in such a way that it already resembled these sections. However, I can also recommend to be more detailed in the preregistration and subsequently prune it into the manuscript, given that manuscripts typically do not contain all the study details that matter.

When the study was conducted, the raw data were stored in a non-proprietary file format and as read-only files. It is important to ensure the file is read-only, so no accidental adjustments would be made to the file and that I could comply with the data policies (i.e., original file always needs to be retained). Saving these raw data as a non-proprietary format meant that I did not save it as an SPSS, Excel, or other commercial format, but as a clear-text file (e.g., a comma separated value (CSV) file). Clear-text files ensure that the data will remain readable in the future, whereas proprietary file formats might not be. Moreover, with clear-text files other people are not required to acquire commercial software packages to read the data.

After having safely stored the data, I cleaned the data in an automated, scripted manner. I conducted my data cleaning in R. I try not to clean data by hand, because I often forget what I have done; scripted data cleaning prevents this entirely. If I do need to manually clean data, the logbook provided by version control is a safety measure to allow the hard route to reproducibility; fully automated data cleaning is in the end the easy route to reproducibility. For example, in this project I had to split responses into separate datapoints, which required a few hours to automate, but doing it manually would have cost me more time and would have made it less reproducible (and more error-prone)

Subsequently I conducted the analyses in R with RMarkdown. RMarkdown allows data analysis and writing to be conjoined into one file. As such, all results were directly generated into the manuscript dynamically. This helped me to prevent errors and to increase the reproducibility of results. For example, the statistical result F(1, 12) = 5.43, p = .037 would not be typed in by hand, but automatically generated with R code. With this we not only enhance reproducibility, but also prevent human errors; in the previous result p = .037 should be p = .038, a simple rounding error which is quickly made. For this project, I had written several specific functions to test for uniformity of p-values that were fabricated when there truly was no effect, to analyze the sampling fluctuation of the variances, and to combine these statistical tools to detect data fabrication. Based on these results, genuine and fabricated data collected were classified as genuine or detected with the statistical tools, which indicated the performance of these methods.

Upon completing the analyses, I requested a co-author to check all the analyses and results (what we call co-piloting). These comments lead to changes in the analysis script (e.g., data handling error), which were not a problem given the dynamic RMarkdown manuscript (another benefit: not having to redo all the numbers in the manuscript). After these errors were revised and checked once more, the manuscript and results were (mostly) reproducible. I typically do a final check to see if everything went as planned and whether all analyses can be run on an independent computer (i.e., whether there are unspecified dependencies).

The final step, prior to submission of the manuscript, is to ensure that the analyses corresponded to the preregistration and that all research files were made publicly available. Research has indicated that researchers who preregister analyses frequently report other analyses, indicating that is easy to forget what you actually planned to do at the start. Cross-checking this allows to pick up on these errors in time. Additionally, I have seen several articles where researchers said they made the research files publicly available, where their files were uploaded (e.g., Github) but not yet made public. These final checks ensure that results are according to the preregistration plan and can be accessed by others.

Pain points

The part of a reproducible workflow that I consider particularly painful is that of co-piloting analysis scripts. It shows when a researcher is reproducible but also shows it can be relatively complex to make reproducibility easy. It can sometimes take an entire day to check a colleague's analyses. However, as reproducibility increases co-piloting becomes less strenuous. Additionally, knowing the particularities of checking other people their work helps improve your own reproducibility. This is why I go through hoops to make sure one file is sufficient to get all the results in the manuscript and that dependencies or datafiles do not cause any trouble.

Another effortful aspect of a reproducible workflow is that the project lead often has to enforce reproducibility. I want my research to be reproducible, so I enforce this in my project. Co-authors need not have the same perspective on this and therefore do not feel responsible for this. As such, you have to ensure that what they do is reproducible as well. If the project has a centralized project lead, this is not a huge problem. However, with more decentralized projects it can cause some difficulty. It requires you to structure the project thoroughly, but requires increasing effort with increasing project complexity (note that increasingly complex projects also have a higher need for reproducibility because of a higher potential for error-making.

Key benefits

My workflow has actively developed in recent years and this has culminated in analysis scripts that can run everything from the script itself. This requires nothing from the person trying to reproduce the results, except to download the script. It can be quite daunting when a researcher shares ten files and you have to find a way through them. It is not sufficient to be transparent. In order to become reproducible, it is highly important to structure your documents such that others, including your future-self, can understand what is going on.

Version control is a benefit within this reproducible workflow, considering that it goes beyond reproducibility of research results but also ensures reproducibility of the research process. My direct colleagues are starting to realize this as well; it is affirming to hear them stress that it helps them increase efficiency by allowing to retrace their steps. I hope that other colleagues will see the value in that sooner rather than later, (e.g., when their data gets audited).

Key tools

I use a set of tools which all have one thing in common: they are based on open formats that are timeless, inclusive, and can be used by anyone who has a computer. These open formats include the data in clear-text files, but also includes software packages that are open-source, whose code is checked by the open-source and academic community (e.g., R, git). It seems to me that the use of closed software has proliferated throughout the social sciences (where I operate most of the time) without the realization that it is actually hurting the future of science (e.g., irreproducibility of results), but also hurts current-day science. Not everybody can afford a license to SPSS or Microsoft Office, for example. Why exclude those who do not have those funds? Science is an enterprise that should be all-inclusive and not select on financial wealth of individuals or institutions. I try to reaffirm this principle by ensuring that all the tools I use are open-source and can be used by anyone who wants to.

Questions

What does "reproducibility" mean to you?

For me, reproducibility pertains to the reliability of research findings, which both includes direct reproducibility (i.e., can someone else reproduce the results by applying the described method to the same data?) and retest reliability (i.e., if we rerun the study, do we get similar results?). My case study focuses on direct reproducibility, that is, that anyone or a future-me can retrace the steps from the project in such a way that it is understandable and that the results are reliable.

Why do you think that reproducibility in your domain is important?

Scientists are humans and humans make mistakes. By using reproducible practices, we can discover these mistakes and not be led down a research path that is based on a mistake. It is important in my domain, because we preach that science has to be conducted in a reproducible manner.

How or where did you learn about reproducibility?

I got interested in reproducible practices during my master education when my supervisor introduced me to the idea of Open Science. I found myself wondering how to implement it in different stages of the research process, not knowing where to start documenting during the research. I learned much from colleagues across the world and across fields with who I discussed ways to be more reproducible (mostly on Twitter, which is a highly valuable resource for researchers).

What do you see as the major challenges to doing reproducible research in your domain, and do you have any suggestions?

Reproducible research is tiresome when you figure out a new way of doing things and then think that your previous work is incomplete. Additionally, not all colleagues are as enthousiastic about reproducibility and this can lead to discussions (also a good thing) that postpone implementing certain practices. It is very important to get everyone on the same page in the initial meeting on how the project will be managed, such that nobody is met with surprises and potential ambivalence at the end.

What do you view as the major incentives for doing reproducible research?

The main incentive for reproducible research is (future) efficiency. When you know that you can revisit projects from years ago and need at most 30 minutes to find what you are looking for is a major improvement over spending a day looking for that one specific value someone asked about in your email. It also helps revisit previous projects and see what I did, because I frequently unlearn things I require in a new project (e.g., I often forget how to make plots in the ggplot2 package because I use it too infrequently, and I just reuse code from previous projects).

Are there any best practices that you'd recommend for researchers in your field?

The best practices I recommend any researcher to apply are the following:

License your work with an open license (CC-BY or CC-0), explicating free reuse of your materials and manuscript.

Script your data handling and analyses as much as possible, such that each step is reproducible.

Have a colleague check your analysis code, it is too easy to make mistakes. Not checking analysis code is comparable to not having co-authors proofread the manuscript.

Try and create an analysis script that can run automatically, downloading all required files and installing its dependencies. Otherwise, other people are likely to fail in reproducing your results, when they cannot get to the dependencies.

Would you recommend any specific resources for learning more about reproducibility?

I recommend the article by Karthik Ram on using version control in research. It opened my eyes on the use of version control as a project management tool that improves reproducibility at the lowest cost possible. Low threshold version control is available at the OSF, which provides online training tools (see osf.io).

Ram, K. (2013). Git can facilitate greater reproducibility and increased transparency in science. Source Code for Biology and Medicine, 8(1), 7.