Using R and Related Tools for Reproducible Research in Archaeology

Ben Marwick

My name is Ben Marwick, and I am an Associate Professor of archaeology in the Department of Anthropology at the University of Washington, and a Senior Research Scientist at the University of Wollongong. My research interests include human-environment adaptations during the Pleistocene in Southeast Asia and Australia. My colleagues and I work with stone artefacts, organic and geological remains to understand past human behaviours and their environmental contexts. My narrative here describes one recent project from the initial concept to a specific publication (Clarkson et al. 2015), but the details below are typical of my experience with several projects focused on understanding prehistoric hunter-gatherer behaviour (cf. Marwick et al. 2016; 2017).

In the context of this case study, reproducibility refers to computational reproducibility, which means enabling other researchers and students to combine the code and data that we produce to obtain the same statistical results and data visualizations that we present in our publication. I also expect that the code could be used for empirical reproducibility, where our code is applied to a new dataset to generate substantively similar results to our published results. I have explored these definitions, and the principles that motivate my selection of tools, in more detail in Marwick (2016).

Workflow

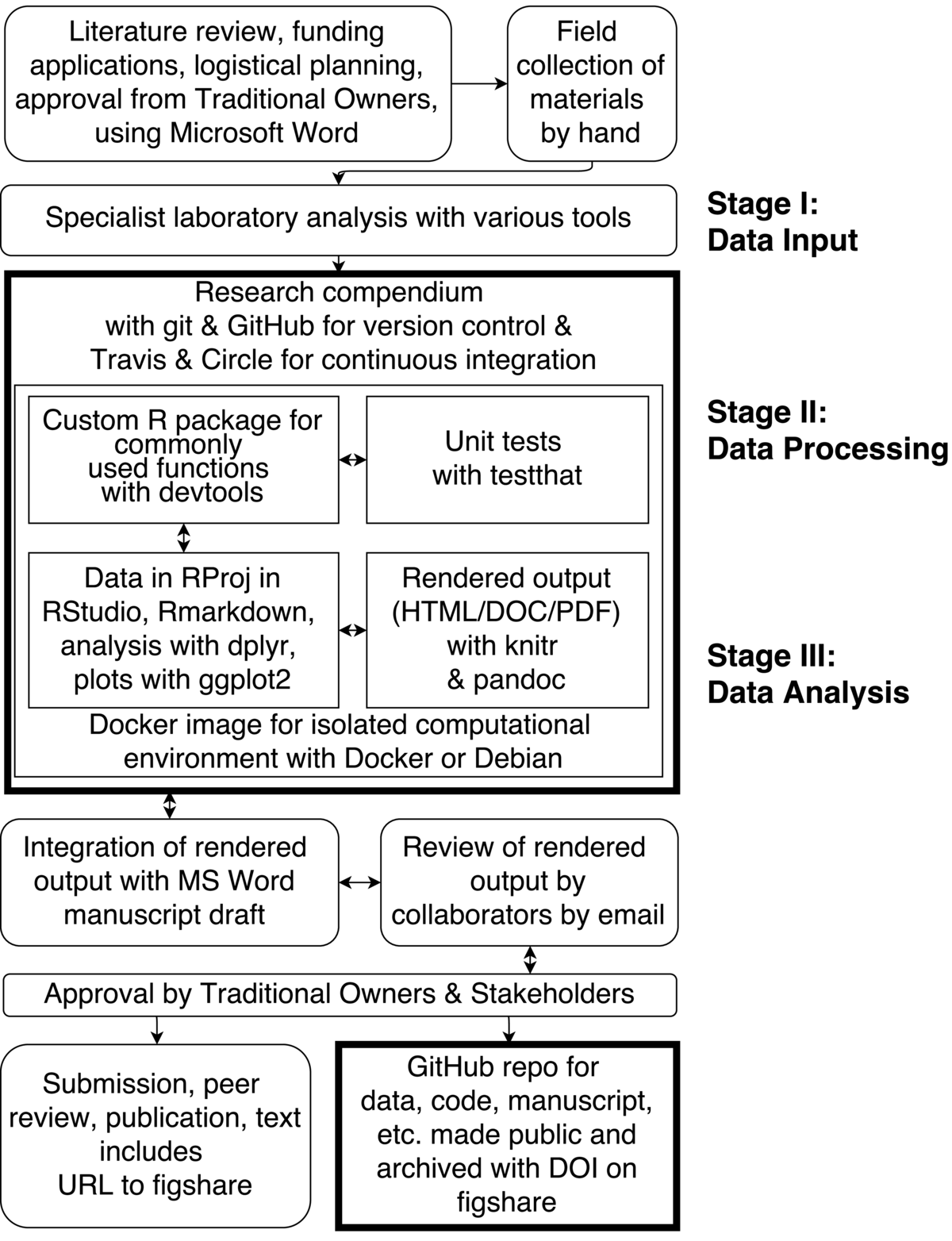

The boxes with a bold outline indicate key steps and tools that enabled computational reproducibility in our project.

The boxes with a bold outline indicate key steps and tools that enabled computational reproducibility in our project.

One recent project I was involved in aimed to excavate Madjedbebe rockshelter, a well-known archaeological site in northern Australia. The purpose of the excavations was to test the findings of previous excavations in the 1990s that uncovered controversial early evidence for human occupation of Australia. The project was initiated with consultation with stakeholders, including Aboriginal traditional owners of the archaeological site, and a grant application written in Microsoft Word and circulated among the team by email.

The archaeological excavation was conducted with standard modern techniques. These include a combination of direct digital capture of artefact and feature provenance with a total station, digital photography and GIS, and hand-written paper notes using structured site recording forms. These data from these forms was later entered into an Excel spreadsheet.

At the conclusion of fieldwork, post-excavation analysis continued at the home institutions of each of the team members. The tools for data collections and analysis at this stage were according to the norms of each lab, but the final products from most of the team members at this stage were MS Word and Excel files. At this point, work began on a manuscript for publication, which was a MS Word document that was circulated among the authors by email.

As the specialist work concluded, the Excel and Word files were collected into an R Project using RStudio. The spreadsheets were converted to CSV files to ensure they could be accessed independent of any specific software. A research compendium was created, based on a custom R package, following the examples described in rrrpkg. This package was written to contain custom functions used often in the analysis. The devtools package was used to develop the custom R package in RStudio. The testthat package was used to write tests to ensure the package functions performed as expected while they were being developed. An R markdown file was created as part of the compendium, and edited in RStudio to recompute and extend the analysis and visualizations from the specialist labs, and combine the key pieces of narrative text from the lab reports that contain statistical results. The R markdown file is a kind of lab note book where code and text are interwoven in a single document. It summarizes and extends the work of the team specialists using R script. The code in the R markdown file used several R packages, including dplyr and reshape2 for data cleaning and analysis, rioja and analogue for specialist environmental methods, and ggplot2 for visualization. The runtimes of the analyses are rarely longer than 30 min, so writing code and narrative, and testing are the most time consuming tasks here.

The R package knitr and the pandoc program (included with RStudio) was used to execute the R markdown file to inspect the output as the code was being written. A Docker container was created to create an isolated computational and portable environment for writing the R markdown document and developing the package. The Docker image was backed up on the Docker Hub server (https://registry.hub.docker.com/u/benmarwick/mjb1989excavationpaper/), and tested using continuous integration from CircleCI. All of these components, data files, R markdown file, package files, etc. were all version controlled using git locally and backed-up on a repository at GitHub. The GitHub repository is here https://github.com/benmarwick/1989-excavation-report-Madjebebe, and a snapshot of this repository at the time of acceptance of our 2015 Journal of Human Evolution paper is archived on figshare here: http://dx.doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.1297059. One of the downsides of using this compendium approach is that most of the work is done by just a few of the team members because not everyone is familiar with (or interested in) the tools.

While the analysis was being developed in the research compendium, a manuscript was being drafted in a MS Word document and circulated among the authors by email, and revised using track changes. The rendered output of R markdown document is also circulated among the authors by email. As the manuscript is updated, and new ideas are incorporated into the analysis, additional code is written, some code abandoned, new plots produced, and others deleted, etc. This is probably the messiest and least ideal part of the workflow as it involves manual updating of the MS Word document with new values and figures from the rendered R markdown document, and two unrelated version control systems (git and track-changes in MS Word). The non-linearity of the process was also challenging, as the authors negotiated how the manuscript and analysis should take shape.

As the review and updating cycle concluded, the manuscript was sent for review by the traditional owners of the land where the archaeological site is located. After this review, which involves some changes to the manuscript, the final draft was prepared for submission. At the same time, the GitHub repository that contains the research compendium was made public and continuous integration from Travis was added to monitor the effect of changes made during peer review. The compendium was also deposited at figshare and the persistent URL to the figshare repository was added to the text of the manuscript as a pointer to the data and code that generated the results and visualizations found in the paper. The MIT license was attached to the code (giving others permission to use and reuse the code), the CC0 license was attached to the data (meaning that the data are in the public domain), and a CC-BY license was attached to the text and figures (meaning that the text is free to use with proper attribution to the original authors). These licenses allow flexible reuse of our materials. The paper was then submitted for publication at the Journal of Human Evolution. At this point the data and software were openly available online for peer reviewers and others to inspect. The code includes the R package, which has documentation about installing the packages and using the functions, has unit tests, and has machine- and human- readable metadata about dependencies. We have also made available the Docker image that contains the compendium in an Linux environment so that all the dependencies external to R can be included in a single bundle.

Pain points

Some of the most notable pain points include:

the inefficiencies of duplication of effort in translating the Excel-based analysis into R, and in moving between MS Word and R markdown for drafting the text. This happens because only a few members of the team are familiar with R and related command-line tools.

the complexities of working on the draft manuscript and updating the analysis as the team explores different options and research directions. This challenges are typical of any large collaborative project, but I think multiplied here because of the 'two universes' of toolkits, with some of the team using Microsoft tools, and others using open source tools. Because of the greater flexibility and efficiency of R over spreadsheets for data analysis, we observed a disempowering of team members who are not familiar with R.

overall, the research compendium is still quite a complex arrangement of tools and scripts, and productive engagement with it requires a high degree of enthusiasm and a high tolerance for trouble-shooting. This is a barrier for collaborators who don't share my interest in reproducibility. However, I'm optimistic that making and using research compendia will become simpler and more normal, and increasing awareness about reproducibility will motivate researchers to take a greater interest in incorporating these practices into their own work.

Key benefits

Some of the advantages that motivated us to pursue that approach include:

A detailed human- and machine-readable record of all the steps in the analysis. This takes the methods out of Microsoft Excel, where they are often invisible due to ephemeral point-and-click behaviours, and reconstructs them in R scripts where every step is explicit. This makes it a lot easier to engage with questions like "can we do that again, but change X a little bit?" and "what happens if we add/exclude Y from the analysis?" This kind of exploratory work is most efficiently done using a scripting language because the equivalent work in a spreadsheet often requires redoing numerous manual steps of data manipulation simply to alter one small step in the analysis pipeline.

An open and transparent record of the analysis for reviewers to inspect, this allows us to say 'we have nothing to hide', and the git repository allows us to show 'we already tried that, and this is what we got' because we have a complete history of our analytical efforts, even those that didn't lead to results included in the publication.

We have a high degree of confidence that our results are correct. We can rerun the analyses repeatedly in an isolated and well-defined environment and get the same result each time.

Our data and methods are available for reuse and application to new projects and contexts by us, and by other researchers and students. This saves time for us in the future, and has the potential to increase the impact of our work.

The uniqueness of our workflow is a double-edged sword because it attracts attention to our project because of its exoticness, but because it's so unfamiliar few people can engage with it or use it in the ways we're hoping. As I developed this workflow I was worried it might be a once-off effort, and that it wouldn't be suitable or sustainable for future projects. Since that time, I've found the opposite to be true -- I've used a similar R-package-as-research-compendium approach as I've described here for subsequent scholarly publications (e.g. Marwick et al. 2016; Marwick et al. 2017). In evolving and simplifying this workflow I've enjoyed substantial gains in efficiency. I've also received a lot of interest in this approach from other groups outside of my discipline who are keen to adopt these practices to improve the reproducibility of their research.

Key tools

The key specialized tool that enhanced the reproducibility of our research is R, and the suite of user-contributed packages that extend its functionality. Many of these add several idioms that greatly improve the ease of use of R, such as dplyr, ggplot2, and knitr. The RStudio program was used to develop the code because it has many built-in conveniences that lower the cognitive burden of package development and coding. Although git and GitHub are not specific to R, use of git is deeply integrated into RStudio, so we consider it part of the R ecosystem. Similarly, Pandoc is a universal document format converter that is not unique to R, but since it is also built into RStudio we consider it part of the ecosystem also.

In addition to R and its ecosystem, we used several popular software engineering tools to help with quality control. These include Docker, a system for lightweight virtual environments (and boot2docker, which enables Docker on Windows and OSX), Travis, which builds and checks our R package each time a commit is made to the GitHub repository, and CircleCI, which is a similar service to build the Docker image and run some simple tests each time a commit is made that changes the dockerfile. We also used these services to render our R markdown documents each time a commit was make, to check that no errors had been accidentally introduced.

While R by itself ('base' R, without contributed packages) is familiar to many social scientists, the packages noted above that introduce powerful modern idioms are less well known. The broader R ecosystem and software engineering tools we used are almost totally unfamiliar to our peers, despite their ubiquity in the software development community. So we see a lot of potential for these tools to be of broader interest, ideally because of the reproducibility they efficiently enable, but likely also because of their novelty.

Questions

Why do you think that reproducibility in your domain is important?

Reproducibility is important because many important steps in our data analysis occur on the researchers' computers, but these steps are often not documented in a way that we can easily access, archive, and communicate with others. The use of software operated by a point-and-click interface is the key problem here. By changing the key analytical tool to a scripting language such as R, we change the nature of our computational work from closed and ephemeral, to open, reusable, and enduring. This makes it a lot easier to show what we've done, why we think the results we present are correct, and enable us and others to reuse and extend our work. These are fundamental for the advancement of science, and with improved reproducibility in our research, we can advance science faster and more reliably.

How or where did you learn about reproducibility?

Most of the reproducible practices in our project were self-taught by a few members in our team adopting practices they've observed in elsewhere, such as ecology and biology. Key resources in this self-teaching include Software Carpentry teaching materials, materials produced by rOpenSci, and instructive scholarly publications and blog posts with code examples, and GitHub repositories written by researchers in other fields who are highly progressive in enabling reproducible research. These include Carl Boettiger, Jenny Bryan, Rich FitzJohn, Karl Broman, and others in the rOpenSci community. Many of the idioms that greatly simplify using R for archaeological data analysis have been contributed by Hadley Wickham and his collaborators on the 'tidyverse' set of packages. The R community on StackOverflow is a great resource because of their strong emphasis on including reproducible examples in questions posted to the site. Many of the questions and problems I encounter have already been answered in several different ways on StackOverflow, often by highly skilled programmers.

What do you see as the major challenges to doing reproducible research in your domain, and do you have any suggestions?

In my field, where the datasets are usually not problematically large and compute times are not inconveniently long, I consider that most of the technology barriers are sufficiently low to be considered solved. The tools are stable, well-documented, and widely used in other domains, so I don't see any major technical challenges. The key challenge is human - not everyone in the team has the skills to use the tools that enable reproducible research, and not everyone has the motivation and opportunity to learn. This contributes to the primary logistical challenge, which is the manual integration of project components using traditional low-reproducibility tools and the components that enable high-reproducibility. My suggestions are to ride the wave of generational change, and teach students and early career researchers about reproducible research as a normal part of doing research. This means teaching them to expect that analyses should be done with a scripting language (rather than point and click), and that code and data from other researchers should be openly available for inspection (rather then 'by request', which when requests are made, are often refused or ignored). This is the long game, waiting for generational change, but I think will be more effective than efforts full of sound and fury to change the entrenched behaviours of senior colleagues, who rarely have the time or inclination to learn new tools and workflows.

What do you view as the major incentives for doing reproducible research?

The major incentives are:

increasing the certainly of the correctness of our results

increasing the ease of tracking our analysis, and exploring new options

increasing the impact of our work by increasing the ability of, and likelihood that, other researchers will use our methods, data and results.

Are there any best practices that you'd recommend for researchers in your field?

The generic practices I'd recommend for researchers in my field include:

making raw data openly available in trustworthy repositories in open formats at the time of publication

using scripts written in a widely used open source programming language to analyze the data

making the scripts openly available in trustworthy repositories so that they can be used with the data to generate the figures and statistical results in the publication.

Would you recommend any specific resources for learning more about reproducibility?

Stodden, V and Miguez, S (2014). Best Practices for Computational Science: Software Infrastructure and Environments for Reproducible and Extensible Research. Journal of Open Research Software 2(1):e21, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/jors.ay

Gandrud, C. (2013). Reproducible Research with R and R Studio. CRC Press. Chicago

rOpenSci Reproducible Science Guide (and see the further readings)

References cited

Clarkson, C., Mike Smith, Ben Marwick, Richard Fullagar, Lynley A. Wallis, Patrick Faulkner, Tiina Manne, Elspeth Hayes, Richard G. Roberts, Zenobia Jacobs, Xavier Carah, Kelsey M. Lowe, Jacqueline Matthews, S. Anna Florin 2015 The archaeology, chronology and stratigraphy of Madjedbebe (Malakunanja II): A site in northern Australia with early occupation. Journal of Human Evolution Volume 83, June 2015, Pages 46–64 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.03.014

Marwick, Ben, Hannah G. Van Vlack, Cyler Conrad, Rasmi Shoocongdej, Cholawit Thongcharoenchaikit and Seungki Kwak (2017) Adaptations to sea level change and transitions to agriculture at Khao Toh Chong rockshelter, Peninsular Thailand. Journal of Archaeological Science 77:94-108. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.10.010

Marwick, Ben, Chris Clarkson, Sue O'Connor and Sophie Collins (2016) Early modern human lithic technology from Jerimalai, East Timor. Journal of Human Evolution 101:45-64. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.004.

Marwick, Ben (2016). Computational reproducibility in archaeological research: Basic principles and a case study of their implementation. Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 1-27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10816-015-9272-9