Problem-Specific Analysis of Molecular Dynamics Trajectories for Biomolecules

Konrad Hinsen

My name is Konrad Hinsen, and I am a researcher at the Centre de Biophysique Moléculaire in Orléans, France. My field of research is molecular biophysics, and in particular the study of the flexibility and dynamics of proteins. All of my work is based on computational approaches, of which the most important ones are elastic network models and Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. Moreover, most of my work concerns the development of computational methods rather than the application of already established methods.

This case study is about the extraction of information from MD simulation trajectories, a very common type of work in my field. MD simulations themselves are relatively standard procedures, performed using one of a handful of well-known software packages. They take a few days to a few weeks on a small parallel computer with a few tens of processors, and produce a so-called trajectory file that is one to ten GB in size. Analyzing these trajectories in order to actually learn something about the system that was simulated is a separate step that is much less standardized, meaning that there is a lot of problem-specific code involved. This code is as much a result of the workflow as the plots of the computed quantities.

For reproducible and publishable workflows, there are three specific challenges in this situation:

The size of the trajectory files, which are difficult to publish in a citeable way, often being larger than the current upper limits of Zenodo or figshare.

There are CPU-intensive tasks that are typically run on a parallel computing cluster in batch mode, and explorative tasks that are done interactively or near-interactively (running short scripts that take about a second) on a desktop machine. Dependency tracking across machines is not supported by most workflow management systems. It doesn't help that computing clusters often have limited network connectivity.

The distinction between "software packages" and "workflows" is not useful when most of the code being executed is problem-specific. A more appropriate code structure is "well-established techniques implemented in libraries", "problem-specific scripts" and at the top level "coordination of a small number of scripts". It's the last two levels that must be captured for reproducibility.

Workflow

A published example of the workflow described below can be consulted in the form of two code/data packages (package 1, package 2) and the article describing the study.

A published example of the workflow described below can be consulted in the form of two code/data packages (package 1, package 2) and the article describing the study.

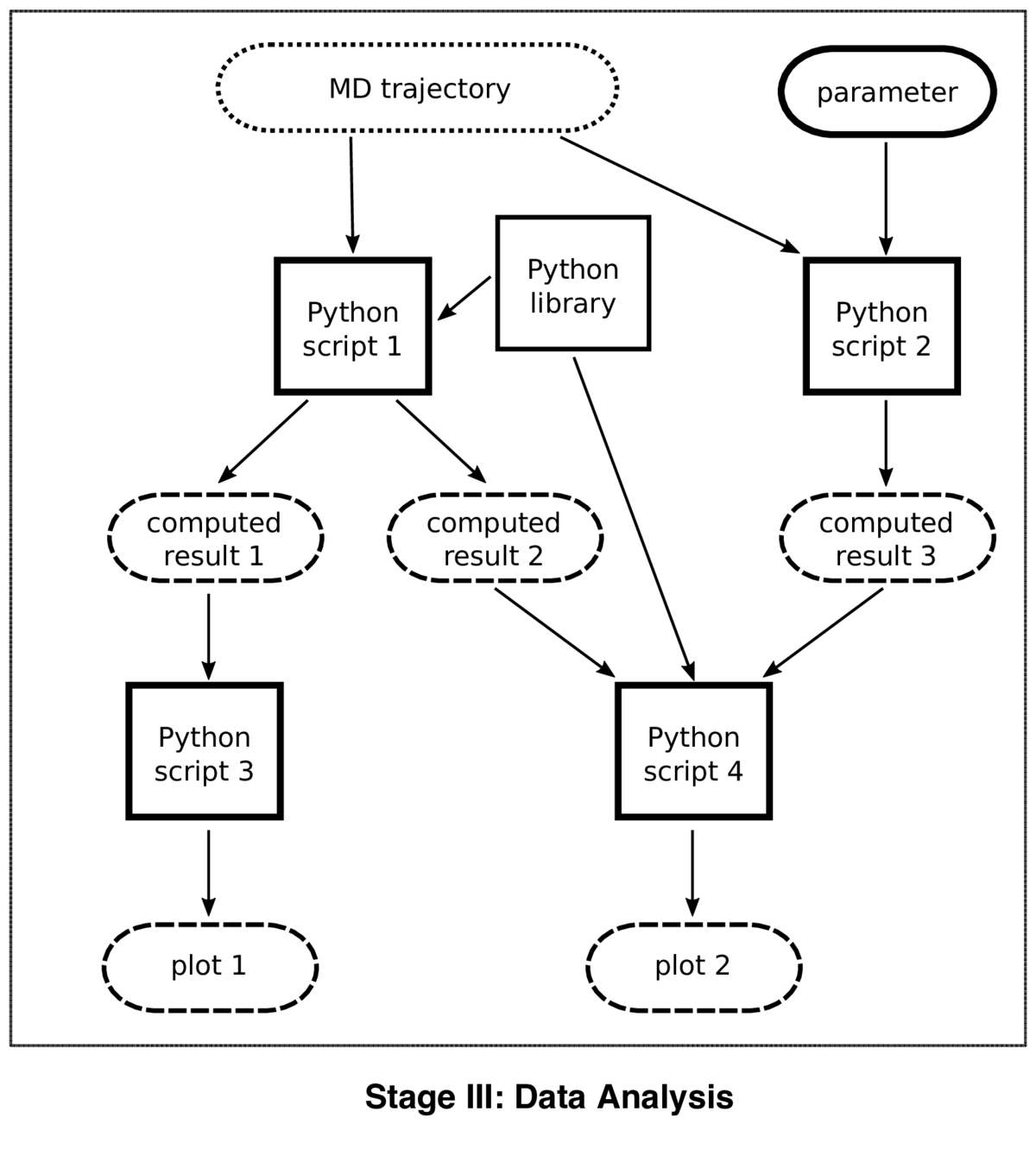

The workflow diagram is actually a dataflow graph with attached workflow information. Compared to most approaches to workflow, which place the tools (workflow manager, software packages, Web services, ...) in the center of attention, the approach I describe here focuses on the data and on the way scientists interact with the data. The workflow below is not about "getting a job done" but about "developping and fine-tuning a scientific model".

The dataflow graph shows code in rectangles, and "passive" data in rounded boxes. Code consists of a small number of Python scripts, of which four are shown in the diagram. Data flows from top to bottom, as shown by the arrows, starting with the MD trajectory that is the overall input, and ending in plots showing computed quantities. The three rounded boxes labelled "computed results" are intermediate results, computed by Python scripts 1 and 2 and consumed by Python scripts 3 and 4.

From the point of view of workflow management and reproducibility, the most important distinction among the data items is "human input" (solid outline) vs. "computed data" (dotted outline). It's the human input that represents the scientific model, and thus the main output of this workflow. It consists of code (Python scripts 1 to 4) and numerical parameters (a single one in the diagram), though that distinction is rather arbitrary: every parameter could be turned into a line in a script. Computed data includes the plots that go into the journal article, but also intermediate results. In a fully reproducible workflow, the computed data need not be stored, because it can be recomputed at any time. Nevertheless, it is often preferable to store it explicitly, in particular if recomputation takes a long time. Stored computed data is also more readily available for exploration by scientists who want to gain a better understanding of the method.

The workflow consists of the iterative refinement of the models and methods. The two key tools in processing the workflow are:

a version control system such as git for keeping track of the changes

the ActivePapers dependency manager for coordinating the computations

Correspondingly, the state of the project consists of

a repository under version control, which tracks the changes to the "human input" items as the project advances

an ActivePaper file, which stores the current state of all data items and the dependency graph

There are two variants of a refinement step: adding a new script or parameter, and modifying existing scripts and parameters. The first kind, which extends the data flow graph, consists of the following user actions:

Write the new script.

Commit it to version control.

Check in the script to the ActivePaper.

Run the script via the ActivePapers dependency manager.

The second kind, which preserves the data flow graph, differs only slightly:

Edit scripts and parameters.

Commit the changes to version control.

Check in the modified versions to the ActivePaper.

Update the ActivePaper.

The fourth step recomputes all data that is affected by the changes made in step 1. The recomputation is steered by the dependency graph, which is obtained from the data flow graph by redirecting arrows that point into a script to point instead to the outputs of the script. The ActivePapers dependency manager computes the dependency graph automatically during the execution of the scripts. Users do not have to deal with (or even know about) either graph explicitly. They write and run scripts as they did before reproducibility became an issue. Similar approaches are used in Sumatra and noWorkflow, but most workflow managers adopt the opposite strategy of letting the user construct a workflow explicitly and then execute it.

A project can be transferred from one computer to another by copying the ActivePaper file and the version control repository. For the common situation in molecular simulations that lengthy computations are off-loaded to a cluster, step 4 in the above procedure is slightly modified: The ActivePaper is sent to the cluster, the "run new script" or "update" operation is performed on the cluster, and the modified ActivePaper file is transferred back to the user's desktop machine. All the tools have a command-line interface, making it easy to use them over an ssh connection.

Method-development projects tend to be small, involving a handful of people. The pitfalls of coordinating modifications to files can easily be avoided by having a single person perform each refinement step, or even all of the refinement steps. Other participants can of course contribute ideas, and inspect the current state of the project for analysis.

At the end of the project, the ActivePaper file(s) can be published, making all of the code and data available to other researchers. The ActivePaper file contains the complete final state of the project (though not its history), meaning that anyone can continue from that state. An ActivePaper file for a new project can re-use items from already published ActivePaper files through a DOI (Digital Object Identifier), allowing other researchers to build on published computational work. The DOI can also be used for citations in journal articles.

Pain points

The main practical difficulty is that most of today's computational scientists grew up with tools and practices that are not compatible with reproducibility. This is particularly true for the field of molecular simulations, where reproducibly published studies are still rare. Working reproducibly requires adopting new tools and habits, and modifying existing software for integration with reprooducble workflows. There is a permanent temptation to give up reproducibility for faster scientific progress.

The immaturity of current workflow tools for reproducible research adds another layer of cognitive overhead. In the workflow described above, this is mainly the use of separate tools for tracking history and dependencies. Today's version control systems, designed for software development rather than computational science, cannot easily be extended by the kind of dependency management required for research. On the other hand, writing new version control software integrated with depenency management represents an effort that is hard to justify at this time.

A major constraint imposed by the ActivePapers system is that all code must be written in Python and all data must be stored in HDF5 datasets. While Python is popular enough for molecular simulation to make the first constraint very acceptable, HDF5 is still a rare choice for data storage, although this is changing thanks to initiatives such as H5MD.

The use of specific tools is rarely sufficient to ensure reproducibility. Tools can only take care of replicability, i.e. the technical aspect of tracking all computational dependencies such that a computation can be re-run identically. Reproducibility at the scientific level requires that all steps can easily be understood and verified by fellow scientists. Best practices for reaching this goal remain to be developed. One observation from the applications of the above workflow is the importance of access to intermediate results for human inspection. This suggests an overall structure of many small scripts that each do a well-defined job and communicate via explicitly stored datasets.

Key benefits

The traditional workflow of changing scripts and running the interactively in a shell is extremely prone to mistakes. The most frequent one is forgetting to re-run a script after its input data has changed because of an update to another script. Before I adopted reproducibility support tools, I regularly found myself looking at a data file and wondering which exact sequence of script executions had produced it. The question typically comes up when writing a paper. Even for today's minimal "materials & methods" sections, it is typically necessary to look up parameters and other choices in the scripts when writing the documentation, and that's often the moment when one discovers what a mess they are. This is no longer an issue when the complete final project state is available for inspection, and guaranteed to be complete and coherent by software tools.

Key tools

The key tool in my workflow is the ActivePapers toolset, which was in fact designed specifically for supporting reproducibility in the context of atomistic and molecular simulations. It supports in particular

computations on large datasets by storing them efficiently in HDF5 files with the dependency information stored as HDF5 metadata

dependency tracking across machines by storing all datasets and their dependency graph in a single HDF5 file that can be copied easily from one machine to another

The only other reproducibility-enabling tool in the workflow is a version control system.

Questions

What does "reproducibility" mean to you?

Given that my work is 100% computational, my long-term goal is full reproducibility, starting from a specification of the simulation and ending with the plots that go into a journal article. This goal is unrealistic at the moment because the simulation software packages do not support reproducibility. One problem is the accumulation of numerical roundoff errors, which are insufficiently standardized across processors and compilers to be reproducible. Another problem is the widespread use of random number generators without user control over the random seed.

For this reason, I have been setting myself a more modest goal for this case study: reproducibility of the trajectory analysis step, using the MD simulation trajectories as input as if they were experimental data outside of my control. This is a useful compromise because the development of trajectory analysis techniques is the central scientific topic of this work.

Why do you think that reproducibility in your domain is important?

Most MD simulation studies are so complex that in the absence of reproducibility, it is impossible to be sure what was really computed. Most mistakes do not lead to a recognizably wrong result, but to a somewhat different one that could well be correct.

How or where did you learn about reproducibility?

I developed them myself, having found nothing suitable for the specific needs of molecular simulations after a careful survey of existing technology and practices.

What do you see as the major challenges to doing reproducible research in your domain, and do you have any suggestions?

The main challenges are human and social. Most of my colleagues have experienced the problems that non-reproducibility creates, but few are willing to invest the extra effort to do a better job, and many remain unaware of the tools and practices for reproducibility that already exist. Journals in my field generally don't require the publication of software or data, and do not in any way encourage reproducibility. Technical challenges exist in that the most popular software packages do not support reproducibility, but the technical challenges could be met with little effort if there were sufficient motivation in the community.

What do you view as the major incentives for doing reproducible research?

Feeling more confident about the correctness of my results.

Being able to build safely on earlier work (by myself or others)

Are there any best practices that you'd recommend for researchers in your field?

I'd already be happy if publishing software and data became the norm in my field. It's hard to recommend any more elaborate practices before the basics become standard.