The Trade-Off Between Reproducibility and Privacy in the Use of Social Media Data to Study Political Behavior

Pablo Barberá

My name is Pablo Barberá, and I am a political scientist who applies computational methods to the study of political and social behavior. I joined the School of International Relations at the University of Southern California as an Assistant Professor in 2016, after spending a year as a Moore-Sloan Fellow at the Center for Data Science in New York University. The workflow I describe here corresponds to part of my dissertation research, whose aim is to study political polarization on social media websites. In particular, here I focus on the research process that led to an article published in the journal Political Analysis in 2015, which presents a new method to estimate the political ideology of Twitter users based on the structure of their personal networks.

Workflow

An important concern in the design of projects involving social media data should be to guarantee that the private records of the individuals in the sample are protected, while ensuring that every step is reproducible. In the analysis described here, I only rely on publicly available information -- in particular, information about Twitter profiles and voting registration records in the state of Ohio, which is used for validation purposes. However, the goal of the project is to infer a sensitive latent trait about each Twitter users -- their ideological position, on a scale from very liberal to very conservative. This is information that most users are not aware could be inferred based only on their public personal information, which raises the question of whether the concept of informed consent in sharing users' data -- as defined in the Terms of Service that users accept when they sign up for a Twitter account -- applies in this context as well.

An important concern in the design of projects involving social media data should be to guarantee that the private records of the individuals in the sample are protected, while ensuring that every step is reproducible. In the analysis described here, I only rely on publicly available information -- in particular, information about Twitter profiles and voting registration records in the state of Ohio, which is used for validation purposes. However, the goal of the project is to infer a sensitive latent trait about each Twitter users -- their ideological position, on a scale from very liberal to very conservative. This is information that most users are not aware could be inferred based only on their public personal information, which raises the question of whether the concept of informed consent in sharing users' data -- as defined in the Terms of Service that users accept when they sign up for a Twitter account -- applies in this context as well.

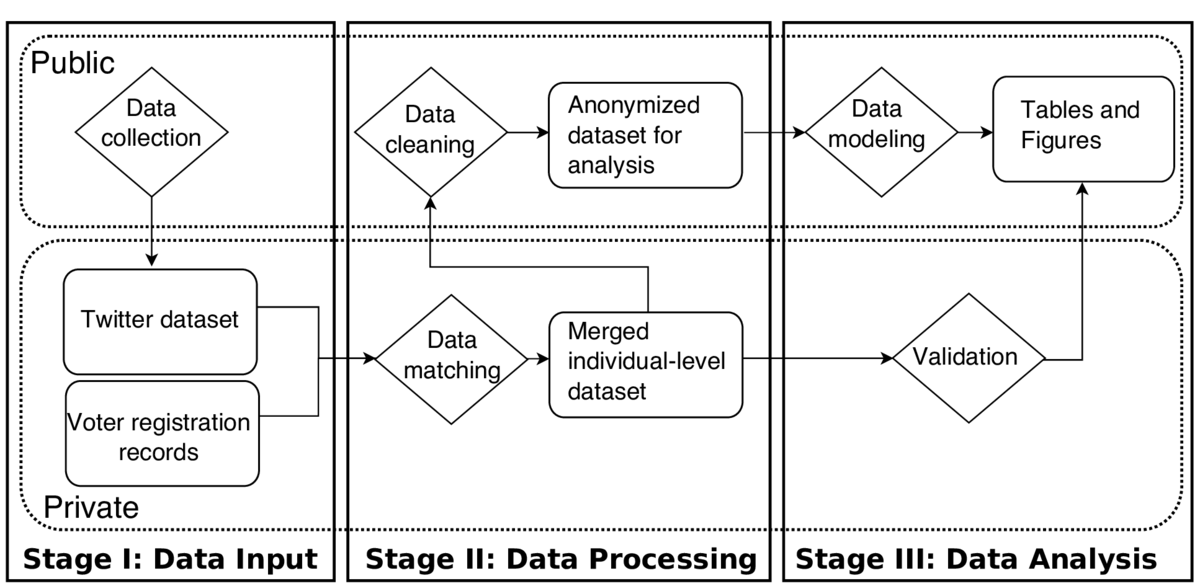

To achieve the goal of reproducibility while adequately protecting users' data, all the analysis in the study takes place at two levels, private and public, as shown in the diagram in this chapter. The private level includes all the original data, which will be processed and merged, and then anonymized so that it can be included in the replication materials. These datasets will not be released, but they can be acquired by other researchers from their original sources. The second level contains all the R code and output (tables and figures), as well as the anonymized version of the dataset, which allows partial replication of the results in the paper even without access to the full dataset. After finalizing the project, the materials in this level were released in public repositories on GitHub and Dataverse.

As shown in the workflow diagram, the first step in the project was to collect a dataset that would allow me to reconstruct the networks of a sample of Twitter users. In particular, I compiled from Twitter's API the lists of followers of a set of around 500 political accounts in the U.S., which includes legislators, candidates, media outlets, etc. Then, I identified the list of users who follow at least three of these political accounts -- this will be the sample in the study. Finally, for each of these users, I also extracted their profile information, including their approximate location, which was parsed into geographic coordinates using the Data Science Toolkit. This data collection step was conducted using R tools developed by the Social Media and Political Participation Lab. All the R code used in this step was made public, but the complete Twitter dataset was stored privately in order to comply with Twitter's terms of service regarding data sharing.

The second step in the workflow involves two types of data processing tasks. First, the user-level information from Twitter was matched with publicly available voting registration records from the state of Ohio, which includes information about the party that each voter is registered with. A Twitter user was matched with a voter whenever there was a perfect and unique match of first name, last name, and county between these two datasets. This information will be used in the validation step in order to assess whether the ideology estimates that result from this method are correlated with offline measures of behavior, such as the number of times that a given voter has participated in a party primary election. The second part of the data processing task involves cleaning the Twitter dataset and building the networks that will be scaled in order to obtain estimates of their ideological positions. In particular, here I constructed an adjacency matrix that indicates whether each of the users in the sample follows each of the political accounts.

After these two steps are completed, I generated an anonymized version of both datasets. The anonymization was achieved by replacing Twitter and voter unique IDs by randomly generated numeric IDs. This will allow researchers to replicate every step of the analysis after this point, but without being able to identify the individuals in the sample.

In the data modeling step, the adjacency matrix that represents this network was scaled using the STAN software for Bayesian modeling using R. The model that was implemented was similar in nature to other latent space models applied to social networks. It builds upon the assumption that the existence of a following link between users and political accounts is inversely related to their distance on a latent ideological dimension. In other words, the intuition of the model is that users tend to follow political accounts that they perceive to be close to their own ideological position. This method returns estimates of the latent positions of both users and political accounts. The output of the model was carefully validated using a variety of offline measures of ideology for both types of actors, including roll-call votes in Congress, aggregate measures of ideology from surveys, and individual-level voting records. One of the strongest results of the paper is that individuals predicted to have the most extreme positions are those that most frequently vote in primary elections -- a clear indication that strength of ideological identities is correlated with strength of partisanship.

After conducting the analysis and validation, the last part of the project consisted of producing a series of tables and figures that summarize the dataset, describe the main results of the paper, and offer a graphical representation of the validation process. All figures and tables were generated using R. Throughout this process, I documented exactly what datasets were required to generate each figure, being careful to ensure that only the code and data available in the public level of the project were required in order to replicate them. These tables and figures were then integrated into the manuscript, written using LaTeX.

Pain points

The replication data and replication code were released in different platforms; the code in GitHub, the data in Dataverse. GitHub provides the ability to track changes in the code, and makes it easy to collaborate. Their online interface is easy to use, which reduces the entry costs for other researchers interested in forking the replication materials for their own projects. However, at the moment GitHub does not allow pushing files over 100 MB. Storing smaller files within this limit is not recommended either, since every change to this file is also stored in the repository. Dataverse, on the other hand, provides a free platform to store large files, with some built-in analysis tools, as well as some basic versioning system. However, it lacks the social layer of GitHub, the ability to collaborate, and a good interface to see differences between files using version control. As a result, at the moment there doesn't exist a single platform that combines the advantages of these two.

A problem that is more specific to the workflow described here is the difficulties in ensuring that the anonymization of private records is complete. As described above, replacing the original Twitter user and voter IDs with randomly generated numbers is an approach that in theory ensures anonymity. In practice, however, it might be possible to discover the identity of some of these individuals using only some of the other variables. For example, if there are unique patterns of following behavior in the dataset (e.g. only one individual follows all the political accounts in the dataset except for Barack Obama), another researcher could succeed at discovering her identity. These are edge cases, which may not occur in the dataset here, but it is a concern if the goal is to guarantee the privacy of all individuals in the sample. Recent developments in the field of cryptography, such as differential privacy, provide promising new methods to improve these research practices.

Key benefits

Most published studies that use social media datasets to study human behavior do not provide replication datasets. This is unfortunate because it represents an important obstacle towards ensuring reproducible scientific practices and limits the use of these materials for learning purposes, but it is also understandable, as the restrictive policies of social media companies imply that researchers need to devote a significant amount of time towards ensuring compliance with these policies. My hope is that the workflow described here can become a blueprint for future replication datasets in this field.

Questions

What does "reproducibility" mean to you?

A study is reproducible when a researcher external to that particular project, but familiar with the literature and methods, is able to obtain identical results by using the same datasets and following the same procedures as those described as in the research output, be it a published article or book. Researchers should also produce replication code and a lab book with more precise details about the analysis conducted as part of the study. However, this should be in addition to the description of the research process in the publication, since the output of running code may depend on software versions, for example. There is also the possibility that a set of results is not "correct," and simply the product of errors in the code or software bugs. In other words, being able to run a piece of code and obtain identical results as those described in a published output is not a necessary nor a sufficient condition for reproducibility.

When applied to studies that rely on social media data, the concept of reproducibility is slightly more nuanced. The Terms of Service of social networking platforms like Twitter or Facebook restrict the distribution of datasets obtained through their Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) for privacy reasons. These companies have taken steps towards enforcing this requirement, including contacting researchers to request they take down replication datasets, even if they were used for research purposes only. The trade-off between ensuring individual privacy and allowing reproducibility is even more evident when social media datasets are combined with survey data or other individual records, as in the case I describe here. In these instances, reproducing a published study implies the additional steps of querying the API to reconstruct the original dataset and matching it with the individual records, which is inefficient and not always possible. The workflow I describe here represents my best attempt towards addressing these challenges and ensuring that other researchers can reproduce my results.